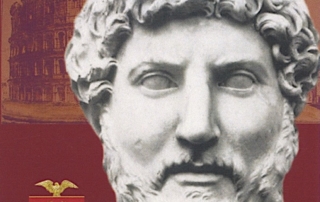

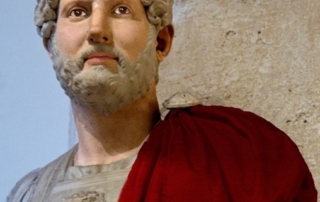

HADRIAN - Publius Aelius Hadrianus

- lived AD 76 – 138

- Emperor AD 117 138

- Peace and Prosperity

- Great patron of the arts

- Passionate traveler

|

|

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadrian_(Kaiser)

SPQR – Senatus Populusque Romanus

.

.

Hadrian is considered one of Rome’s most brilliant rulers.

He was an expert in math, music, painting, poetry, military affairs, and debate.

He ruled Rome at one of its most happy and prosperous periods.

He was a lavish builder, an avid traveler.

.

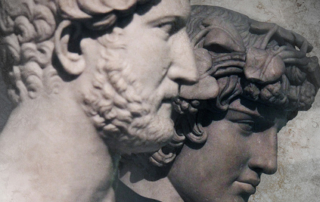

He wrote poetry about the love and it was his devotion to this love that inspired the construction of the greatest monument to love ever built, Antinoopolis. Not much is known about their relationship. There are some reliefs of the couple hunting. Including one that shows a lion hunt in Libya. Of this episode the Alexandrian poet Panacrates wrote an account. Apparently an especially mean lion had been terrorizing people and Hadrian went to slay it. He threw his spear but deliberately only wounded the animal to let Antinous deal the death blow but the lion attacked before the young man had a chance and the emperor killed the lion saving his lover’s life. But it was a life sadly destined to be short lived.

There is a debate around the death of Antinous. All we know for sure is Antinous “fell” into the Nile. But the word “fell” can be translated as an accident or a sacrifice. It is possible that the young man accidentally fell into the Nile, but some say the emperor could have been preparing a ritual to extend his life that demanded a sacrifice and no one but his lover would volunteer.

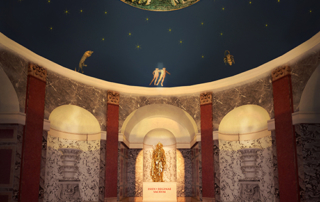

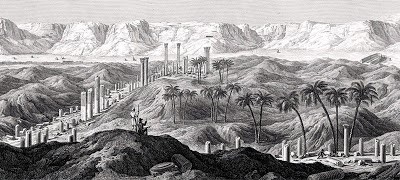

Either way Hadrian was so upset by the loss of his love that we are told he “cried like a woman” and resolved to erect a city in Antinous’ honor. On October 30th 130 Hadrian issued an edict that this new city should be a monument to the dead boy, and a religious shrine. Antinoopolis, the city of gay love flourished for centuries surviving Christianity and the Arab occupation of Egypt.

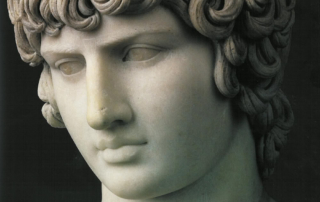

Hadrian even went so far as to have his lover declared an immortal deity which was apparently not uncommon practice back then for noble people to do, but Antinous was a commoner. Nonetheless images of the beautiful youth-god are widespread. He was considered in relation to the Egyptian deity Osiris as on who died and was resurrected and grants the requests those make of him. For this he was also compared to Christ. The religion of Antinous was very popular and widespread and it survived Hadrian’s death by several centuries, and Archaeologists found over half a million jars that held offerings to the shrine at Antinoopolis.

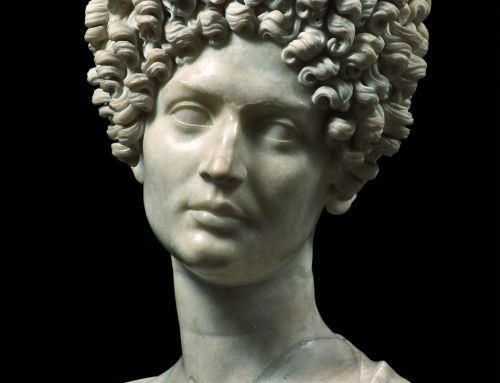

When the ruins of Antinoopolis were surveyed in 1798 by Edme-Francois Jomard 1,344 statues of the young man were found. And the existing statues of Antinous are considered some of the greatest works of art ever!

Unfortunately the ruins of Antinoopolis were lost sometime between 1798 and 1863 to an Egyptian construction company who ground the city’s many pillars into cement. Industry made powder of the greatest shrine ever built to love.

If only love were the motivator behind more construction and development. I can imagine gorgeous cities brimming with the love feeling. I can picture buildings bedecked with depictions of lovers entwined, statues of handsome men abounding, sexually suggestive fountains gushing. I see an entire reordering of society coming from love rather than from greed and the desire for power.

Within hours of taking the throne, in August AD117, the emperor Hadrian made one major strategic decision. He issued the order to withdraw the Roman troops from Iraq (or Mesopotamia, as he would have called it). His succession had been a messy one, in the usual Roman way. Despite a well-earned reputation for effective administration in most areas, the Romans never really sorted out the transfer of imperial power. Hadrian’s leadership bid was more reminiscent of what goes on in the Labour party than in the House of Windsor. It involved a good deal of manipulation, double-dealing, back-stabbing (in Rome this was real, not metaphorical) and perfect timing. A couple of rivals had made their bid too soon, leaving Hadrian as the only plausible candidate to be adopted by his elderly predecessor Trajan, just a few days before he died.

For Hadrian himself has long seemed a familiar figure in many other respects. He is not exactly „one of us“, perhaps, but he is at least one of those rare characters from the Roman world to whom even now we can feel quite close. In contrast to the sheer madness of Nero or Caligula, or to the disconcerting and implausible probity of the first emperor Augustus, Hadrian is the kind of political leader whose behaviour seems distinctly recognisable, whose ambitions and conflicts we can almost share.

There are all kinds of ways in which Hadrian’s life and interests seem to match up to our own expectations of monarchs and world leaders, and to modern interests and passions. He was the sponsor of Mitterand-style grands projets, a great traveller to the outposts of his dominion (including that trip to Britain), as well as an enthusiastic collector of art. And to cap it all, he had an intriguing, and ultimately tragic, sex life.

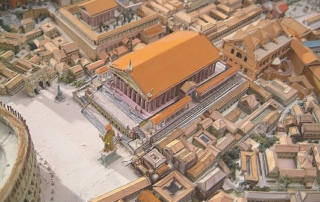

The British Museum exhibition made a good deal of his building work and his art collecting. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, given that the museum itself is the descendant and direct beneficiary of Hadrian’s passion for architectural design and classical sculpture. His most famous building in Rome was the great Pantheon. One of the few ancient Roman buildings to remain standing to its full height, and even now in active use as a church, it is crowned with what is still the largest dome ever built with unreinforced concrete. This has been the inspiration behind almost every great dome built since, from St Sophia in Istanbul (a grand projet of one of Hadrian’s eastern successors, the emperor Justinian) to the dome of the museum’s own round reading room. By a nice symmetry, it is here that the Hadrian exhibition has been displayed – placing the emperor, so to speak, in his own dome.

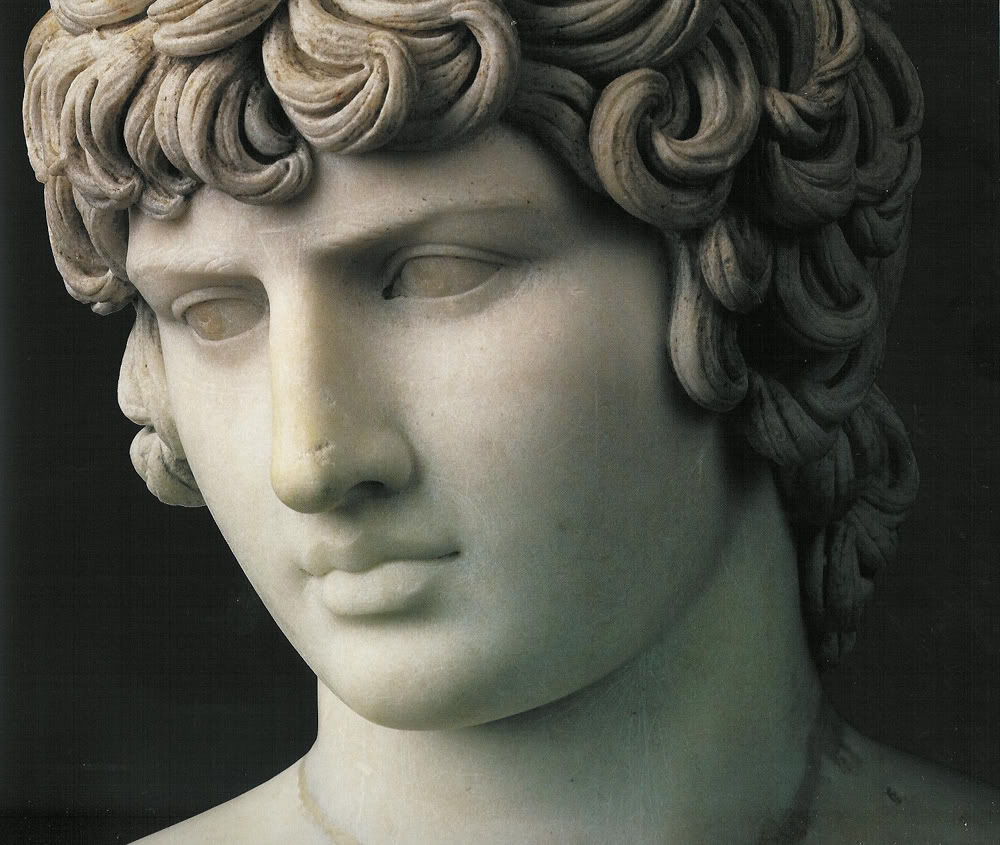

Another major theme of the new show is Hadrian’s relationship with Antinous, a boy who came from Bithynia, in modern Turkey. We know no details whatsoever of what went on between the two, but the usual story – misogynist as so many such stories are – contrasts the emperor’s passion for this beautiful lad with the loveless, childless marriage to his bad-tempered and scheming wife, Sabina. What is certain is that Antinous died young, drowned in AD130 in the River Nile (murder, esoteric sacrifice, suicide and tragic accident have all been suspected), and that following his death Hadrian devoted enormous energies to his commemoration. He had him made into a god. He founded and named a city after him, Antinoopolis, on the banks of the Nile where the boy had drowned. At Tivoli, near one of the main entrance-ways to the palace, he greeted visitors with an elaborate cenotaph for Antinous, in distinctive Egyptian style – complete, it seems, with palm trees.

He also flooded the Roman world with his statues. About a hundred portraits of Antinous are known, more than we have for any other individual Roman, apart from the first emperor Augustus and Hadrian himself. These come in all shapes, sizes and styles, from colossal images in the guise of an Egyptian god to precious miniatures in silver. But the standard, instantly recognisable type is of a languorous young man, pouting, heavy-lipped and sultry – an image that has come to be almost a shorthand for „sex in stone“. It is perhaps no surprise that JJ Winckelmann, the 18th-century art historian, archaeologist and homosexual, steamed over one particular sculpture of the boy in a private collection in Rome. In fact, the most famous portrait of Winckelmann shows him studying an engraving of that very statue. But even now the sight of Antinous can work its magic. One of the portrait heads in the British Museum exhibition is a vast sculpture from the Louvre, known as the „Mondragone Antinous“, after the place in Italy where it was first put on show in the early 18th century. Although a few recent critics have gone against the grain and deemed it a faintly repulsive, pouting monstrosity, others have made no secret of their admiration. When it was unpacked from its crate in Leeds a few years ago, where it was due to star in an exhibition devoted to Antinous at the Henry Moore Institute, it bore on its cheek the clear traces of a bright red lipstick kiss.

Traveller, patron, grief-stricken lover, art collector, clear-thinking military strategist. How do we explain why Hadrian seems so approachably modern? Why does he seem so much easier to understand than Nero or Augustus? As so often with characters from the ancient world, the answer lies more in the kind of evidence we have for his life than in the kind of person he really was. The modern Hadrian is the product of two things: on the one hand, a series of vivid and evocative images and material remains (from portrait heads and stunning building schemes to our own dilapidated wall); on the other, the glaring lack of any detailed, still less reliable, account from the ancient world of what happened in his reign, or of what kind of man he was, or what motivated him.

The only fully surviving ancient biography is a short (20 pages or so) life – one of a series of colourful but flagrantly unreliable biographies of Roman emperors and princes written by person or persons unknown, sometime in the fourth or fifth centuries AD. This includes one or two nice anecdotes, which may or may not reflect an authentic tradition about Hadrian. My own particular favourite features his visits to the public baths. The story goes that on one occasion Hadrian spotted a veteran soldier rubbing his back against the marble wall. When he inquired why he did this, the old man replied that he could not afford a slave. So Hadrian presented him with some slaves, and with the money for their upkeep. On his next visit, there was a whole crowd of old men rubbing their backs against the wall. Far from repeating his gift, he suggested that they take it in turns to rub each other down. There were a number of morals here. Hadrian was a man of the people, not above mixing with the plebs in the public baths. He had his eyes open for his subjects‘ genuine distress and personally intervened to help. But you couldn’t take him for a ride.

Sadly, very little of the life is up to this quality. Most of it is a garbled confection, weaving together without much regard for chronology allegations of conspiracies, accounts of palace intrigue, and vendettas on Hadrian’s part – plus an assortment of curious facts and personal titbits (his beard, it is claimed, was worn to cover up his bad skin). To fill the gaps, to make a coherent story out of the extraordinary material remains of his reign, to explain what drove the man, modern writers have been forced back on to their prejudices and familiarising assumptions about Roman imperial power and personalities. So, for example, where – thanks to the surviving ancient literary accounts – it has been impossible to see Nero as anything other than a rapacious megalomaniac, Hadrian has morphed conveniently into cultured art collector and amateur architect. Where Nero’s relationships with men have to be seen as part of the corruption of his reign, Hadrian has been turned into a troubled gay. Hadrian seems familiar to us – for we have made him so.

How the myth of a Roman emperor has been created – and continues to be created – out of our own imagination and the dazzling but sometimes puzzling array of statues, silver plates and lost keys of slaughtered Jewish freedom-fighters.